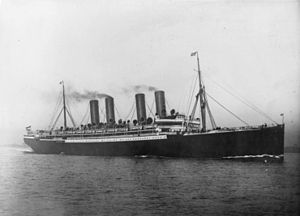

SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse |

| Namesake | William I, German Emperor |

| Owner | North German Lloyd |

| Port of registry | |

| Builder | Stettiner Vulcan, Stettin |

| Laid down | 1896 |

| Launched | 4 May 1897 |

| Christened | 4 May 1897 |

| Maiden voyage | 19 September 1897 |

| In service | 1897–1914 |

| Out of service | 26 August 1914 |

| Refit | 1913 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Scuttled in battle, 26 August 1914 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Kaiser-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 14,349 GRT, 5,521 NRT |

| Displacement | 24,300 long tons (24,700 t) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 66.0 ft (20.1 m) |

| Draft | 27 ft 11 in (8.51 m) |

| Depth | 35.8 ft (10.9 m) |

| Decks | 4 |

| Installed power | 3,094 NHP, 33,000 ihp (25,000 kW) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 22.5 kn (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph) |

| Capacity | 1,506 passengers |

| Crew | 488 |

| Armament |

|

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse ("Emperor William the Great") was a German transatlantic ocean liner in service from 1897 to 1914, when she was scuttled in battle. She was the largest ship in the world for a time, and held the Blue Riband until Cunard Line’s RMS Lusitania entered service in 1907. The vessel’s career was relatively uneventful, despite a refit in 1913.

The liner was built in Stettin for Norddeutscher Lloyd, and entered service in 1897. She was the first liner to be a Four funnel liner and is considered to be the first "super liner."[1] The first of four sister ships built between 1903 and 1907 for Norddeutscher Lloyd (the others being Kronprinz Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II and Kronprinzessin Cecilie), she marked the beginning of a change in the way maritime supremacy was demonstrated in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century.

The ship began a new era in ocean travel and the novelty of having four funnels was quickly associated with size, strength, speed and above all luxury. Quickly established on the Atlantic, she gained the Blue Riband for Germany, a notable prize for the fastest trip from Europe to America which had been previously dominated by the British.

In 1900, she was damaged in a massive and lethal multi-ship fire in the port of New York. She was also in a collision in the French port of Cherbourg in 1906. With the advent of her sister ships, she was modified to an all-third-class ship to take advantage of the lucrative immigrant market travelling to the United States.

Converted into an auxiliary cruiser at the outbreak of World War I, she was given orders to capture and destroy enemy ships. She destroyed several before being defeated in the Battle of Río de Oro by the British cruiser HMS Highflyer and scuttled by her crew, just three weeks after the outbreak of war. Her wreck was discovered in 1952 and partly dismantled.

Origin, concept and construction

[edit]

At the end of the 19th century, the United Kingdom dominated maritime trade with the ocean liners of the principal maritime companies such as the Cunard and the White Star Line. Having gained more influence in Europe after William I, German Emperor, his grandfather, had created the German Empire in 1871, Emperor Wilhelm II wished to consolidate German influence on the sea and thus decrease that of the British.[2] In 1889, the Emperor himself had attended a naval review in honour of the jubilee of his grandmother Queen Victoria. There he saw the strength and size of these British ships, notably the latest and then-largest liner owned by White Star, RMS Teutonic. He particularly admired the fact that these ships could easily be converted to auxiliary cruisers in time of conflict. Leaving a lasting impression, the emperor was heard to say that "We must have some of these..."[3]

Norddeutscher Lloyd, commonly called NDL, or in English, North German Lloyd, was one of only two German maritime companies which had any influence in the hugely profitable North Atlantic shipping market. Neither of these lines had shown any interest in operating large liners. NDL, however, was the first company to name any of their liners in honour of members of the Imperial family, purely to flatter the emperor. The company also had important links with the naval architects AG Vulkan of Stettin. NDL then approached Vulkan and commissioned them to build a new "superliner", which was to be named Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. The new ship would set a new style for ocean liners. She was the largest and longest liner afloat and would have been the largest ever had it not been for Great Eastern of 1860.[4] She was the first liner to have suites with sleeping quarters including a private parlor and bath. She was built with decks strengthened to mount eight 15 cm (5.9 in) guns, four 12 cm (4.7 in) guns, and fourteen machine guns; although fewer and smaller guns were actually mounted in her ultimate wartime conversion.[5]

The launching of the ship took place on 4 May 1897 in the presence of the Imperial family; it was the emperor who baptised the ship whose name honoured his grandfather Emperor William I, "the Great". The liner was completed and internally decorated at Bremerhaven. Her maiden voyage was scheduled for September the same year.[6] Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was the first ship to have four funnels. For the next two decades they were a symbol of size and safety.

Characteristics

[edit]Technical aspects

[edit]Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse's registered length was 627.4 ft (191.2 m), her beam was 66.0 ft (20.1 m) and her depth was 35.8 ft (10.9 m). Her tonnages were 14,349 GRT, 5,521 NRT[7] and 24,300 long tons (24,700 t) displacement.[8] Her dimensions were similar to those of the 1860 Great Eastern, which was the largest ship of its time.[9] As already noted, her four funnels were her most unusual feature. People associated the safety of an ocean liner with the number of "stacks" or funnels they had. Some passengers would in fact refuse to board ships if they did not have four funnels.[10] In an age when ocean travel was not as safe as today, it was important to ensure that passengers felt at ease.[11]

The special improvement in the arrangement of this steamer, as compared with other express steamers previously built by the NDL or other companies, consisted in the entire upper deck.[12] Like many four-funnelled liners, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse did not actually require that many. She had only two uptake shafts from the boiler rooms, which each branched into two to connect to the four funnels—this design is the reason for the funnels being unequally spaced.[10]

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse became the first liner to have a commercial wireless telegraphy system when the Marconi Company installed one in February 1900.[9] Communications were demonstrated with systems installed at the Borkum Island lighthouse and Borkum Riff lightship 30 km (16 nmi; 19 mi) northwest of the island, as well as with British stations,[9] and the first ship-to-shore message was sent on 7 March.[13] By 1911 her call sign was DKW.[14]

The ship was propelled by two had two 22 ft 3.75 in (6.8 m) propellers,[15] each powered by a four-cylinder triple expansion engine. Between them her two engines were rated at 3,094 NHP[7] and gave her a speed of more than 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph).[16] The engines were noted for their stability.[17] The engines were balanced on the Schlick system, which prevented movement being transferred to the body of the ship, thus reducing vibration.

Interiors

[edit]

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was built to carry a maximum of 1,506 passengers: 206 first class; 226 second class; 1,074 third class. When she was completed, her crew numbered 488. However, after her refit in 1913, her crew space was increased to 800. The décor of ship was in the style of Baroque revival, overseen by Johann Poppe, who carried out all of the interior decoration. This was unique as usually a ship would have several interior designers.[18]

The interiors were graced with statues, mirrors, tapestries, gilding, and various portraits of the Imperial family. The interiors of her sister ships were also placed in the hands of Poppe. The first class salon was noted for its tapestries and its blue seating.[19] The smoking room, a traditionally male preserve, was made to look like a typical German inn.[20] The dining room, capable of holding all passengers in one sitting, rose several decks and was crowned with a dome. The room also had columns and had its chairs fixed to the deck, a typical feature of ocean liners of the era.[21]

Career

[edit]

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse set out on her maiden voyage on 19 September 1897, travelling from Bremerhaven to Southampton and thence to New York.[12] With a capacity of 800 third-class passengers, the NDL had ensured that they would profit greatly from migrants from Europe to the United States. From her maiden voyage, she was the only superliner to cross the Atlantic with such speed and such media attention. In March 1898,[12] she successfully gained the Blue Riband with an average crossing speed of 22.3 kn (41.3 km/h; 25.7 mph), thus establishing the new German competitiveness.[22] The Blue Riband, an award given for the fastest crossing of the North Atlantic, east and westbound, had previously been held by the Cunard liner RMS Lucania.[23] This turn of events was closely watched by the maritime world of the era, who were eager to see how the British would retaliate.[24] However, the NDL soon lost the riband in 1900 to the new German superliner, Deutschland of the Hamburg America Line.[25] This change in events was acceptable to Germans, who were able to relax in the knowledge that they were still the owners of the fastest liner; however, NDL promptly ordered that Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse undergo a refit to ensure that they were the dominant German company.[26] This refit included the installation of wireless telegraphy, then new technology which allowed Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse to transmit telegraphic messages to a port, emphasising her image of security.[27]

The NDL took the competition even further. 1901 saw the addition to their fleet of another four-funnel liner, named Kronprinz Wilhelm in honour of Crown Prince William, heir to the German throne, and they subsequently commissioned another two superliners, Kaiser Wilhelm II and Kronprinzessin Cecilie of 1903 and 1907 respectively.[28] From 1904 to 1907 the east-bound speed rekord was held by SS Kaiser Wilhelm II. The company stated that the four liners were of the renowned Kaiser class and decided to market them as the Four Flyers, a reference to their speed and associations with the Blue Riband.[29]

In June 1900 at her quay in Hoboken, New Jersey, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was the victim of a fire which killed one hundred staff who were trying to remove the threat[30] as the ship was towed to safety in the Hudson River.[5] Six years later, on 21 November 1906, she was in collision with the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company liner RMS Orinoco in Cherbourg Harbour. Five passengers aboard Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and three crewmen aboard Orinoco were killed, and Orinoco's clipper bow made a 8 m (26 ft) tear in the starboard side of Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse's hull.[18][31] A court of inquiry found Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse wholly responsible for the collision.[32] New York City mayor William Jay Gaynor was embarking on a European vacation when he was shot aboard the ship on 9 August 1910.[5]

A technological evolution of steamships soon made NDL's express steamers outdated. Cunard's RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania outmatched their German rivals in all fields, and when the future White Star's RMS Olympic entered service in 1911, luxury on the high seas was taken one step further. As a result, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was rebuilt in 1913 to carry third-class passengers only. It seemed that her glory was fading regardless of her career as the first "four stacker".[16] From 26 January 1907, she was charged with carrying passengers between the Mediterranean Sea and New York, effectively ending the public career of the first of the "four flyers".[citation needed]

World War I

[edit]From 1908, German naval captains had been receiving orders to make preparations in the event of a sudden war. In fact, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was soon fitted with cannons and thus transformed into an auxiliary cruiser.[16] Across the world, supply ships carrying weapons and provisions were ready to convert merchant vessels into armed auxiliary cruisers. On 4 August 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany after the Germans invaded Belgium and Luxembourg. Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was requisitioned and turned into an armed cruiser, painted in grey and black. Her commander at the time, Captain Reymann, operated not only under the rules of war, but also the rules of mercy.[16][dead link]

Reymann soon sank three ships, Tubal Cain, Kaipara, and Nyanza, but only after taking their occupants on board. Further south in the Atlantic, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse encountered two passenger liners: Galician and Arlanza.[16] Reymann's first intention was to sink both vessels, but, discovering that they had many women and children on board, he let them go. In this early stage of the war, it was thought that it could be fought in a chivalrous fashion. However, soon it was to become a total war and ships would no longer be warned before being fired upon. As Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse approached the west coast of Africa, her coal bunkers were almost empty and needed refilling. She stopped at Río de Oro, (Villa Cisneros, former Spanish Sahara) where German and Austrian colliers started the task of refuelling her.[16][33]

The task of coaling was still going on on 26 August, when the British cruiser HMS Highflyer appeared. Reymann quickly prepared his ship and crew for battle and steamed out to engage the enemy after disembarking his prisoners of war. A fierce battle took place, but came to a dramatic end when Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse ran out of ammunition.[16] According to the Germans, rather than let the enemy capture the onetime pride of Germany, Reymann ordered the ship to be scuttled using dynamite, which was already in position should this situation ever arise. On detonation, the explosives tore a massive hole in the ship, causing her to capsize. This version of events was disputed by the British, who stated that Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse had been badly damaged and sinking when Reymann ordered it to be abandoned. The British firmly believed that it was gunfire from HMS Highflyer which sank the German ship.[34] Reymann managed to swim to shore, and he made his way back to Germany by working as a stoker on a neutral vessel. Most of the crew were taken prisoner and held in the Amherst Internment Camp in Nova Scotia for the remainder of the war.

The downfall of such great liners in the event of war was their huge fuel consumption. Most liners were subsequently converted from cruisers to hospital ships or troopships.[35]

Wreck

[edit]On 6 September 2013, the Salam Association for the Protection of the Environment and Sustainable Development in Morocco captured underwater footage of what was left of the wreck, with the ship's name on the hull visible. This was confirmed by the Moroccan Ministry of Culture on 8 October 2013.

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Miller (1987), pp. 11–13.

- ^ Mars, p. 36

- ^ « Teutonic » Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Ocean Liners. 15 July 2010

- ^ Ferulli, p. 117

- ^ a b c Halsey, Francis Whiting (1920). History of the World War. Vol. Ten. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. pp. 15–17.

- ^ Ferulli, p. 116

- ^ a b Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping, 1898, KAI–KAL

- ^ Schmalenbach, p. 48

- ^ a b c Ferulli, p. 118

- ^ a b Miller, p. 4

- ^ Ferulli, p. 119

- ^ a b c Miller, p. 2

- ^ "Messages from a Vessel". The New York Times. 8 March 1900. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ The Marconi Press Agency Ltd, p. 238

- ^ "The Monetary Times". Toronto.

- ^ a b c d e f g "SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, The Great Ocean Liners". The Great Ocean Liners. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ « SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, Norddeutscher Lloyd », Norway Heritage. Consulté le 15 July 2010

- ^ a b Le Goff, p. 22

- ^ Server, p. 19

- ^ Piouffre, p. 108

- ^ Piouffre, p. 110

- ^ Mars, p. 47

- ^ Mars, p. 39

- ^ Piouffre, p. 109

- ^ Le Goff, p. 25

- ^ Burgess, p. 36

- ^ Le Goff, p. 23

- ^ Ferulli, p. 121

- ^ SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie » Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Ocean Liners. 15 July 2010

- ^ Server, p. 43

- ^ "Orinoco". Clyde Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Nicol, p. 226

- ^ Ferulli, p. 120

- ^ Kludas' Great Passenger Ships of the World

- ^ Burgess, p. 231

Sources

[edit]- Burgess. Douglas D. Seize the Trident: The race for superliner supremacy and how it altered the Great War. McGraw-Hill Professional, 1999. ISBN 9780071430098

- Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Volume I. – Steamers. London, Lloyd's Register of Shipping, 1898.

- The Marconi Press Agency Ltd The Year Book of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony. London, The St Katherine Press, 1913.

- Miller, William H. The First Great Ocean Liners in Photographs. Courier Dover Publications, 1984. ISBN 9780486245744

- Miller, William H. Famous Ocean Liners. Patrick Stephens, 1987. ISBN 0 85059 876 1.

- (in French) Ferulli, Corrado. Au cœur des bateaux de légende. Hachette Collections. 1998. ISBN 9782846343503

- Nicol, Stuart. MacQueen's Legacy; A History of the Royal Mail Line. Volume One. Brimscombe Port and Charleston, SC: Tempus Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7524-2118-2

- (in French) Le Goff, Olivier Les Plus Beaux Paquebots du Monde. ISBN 9782263027994

- (in French) Mars, Christian. Paquebots. Sélection du Reader's Digest. 2001. ISBN 9782709812863

- (in French) Piouffre, Gérard. L'Âge d'or des voyages en paquebot. Éditions du Chêne. 2009. ISBN 9782812300028

- (in French) Server, Lee. Âge d'or des paquebots. MLP. 1998. ISBN 2-7434-1050-7

- (in German) Trennheuser, Mattias Die innenarchitektonische Ausstattung deutscher Passagierschiffe zwischen 1880 und 1940. Hauschild-Verlag, Bremen 2010. ISBN 978-3-89757-305-5.

External links

[edit]- El trasatlántico "Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse" un express liner del siglo XIX Archived 25 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Spanish)

![]() Media related to SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse at Wikimedia Commons

- Ships of Norddeutscher Lloyd

- World War I cruisers of Germany

- World War I commerce raiders

- Auxiliary cruisers of the Imperial German Navy

- World War I passenger ships of Germany

- Blue Riband holders

- Kaiser-class ocean liners

- Four funnel liners

- 1897 ships

- Ships built in Stettin

- Maritime incidents in 1900

- Ship fires

- Maritime incidents in August 1914

- Scuttled vessels of Germany

- World War I shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean