Tannic acid

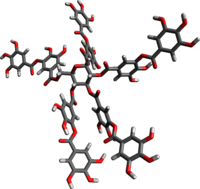

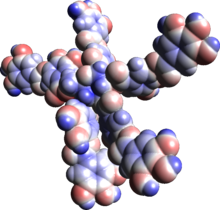

Chemical structure of penta(digalloyl)glucose, a representative component of tannic acid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-{3,4-dihydroxy-5-[(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoyl)oxy]benzoyl}-D-glucopyranose

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

2,3-dihydroxy-5-({[(2R,3R,4S,5R,6R)-3,4,5,6-tetrakis({3,4-dihydroxy-5-[(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)carbonyloxy]phenyl}carbonyloxy)oxan-2-yl]methoxy}carbonyl)phenyl 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 8186386 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.321 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C76H52O46 | |

| Molar mass | 1701.19 g/mol |

| Density | 2.12g/cm3 |

| Melting point | decomposes above 200 °C |

| 2850 g/L or 250 g/L[1][2] | |

| Solubility | 100 g/L in ethanol 1 g/L in glycerol and acetone insoluble in benzene, chloroform, diethyl ether, petroleum, carbon disulfide, carbon tetrachloride. |

| Acidity (pKa) | ca. 6 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Tannic acid is a specific form of tannin, a type of polyphenol. Its weak acidity (pKa around 6) is due to the numerous phenol groups in the structure. The chemical formula for commercial tannic acid is often given as C76H52O46, which corresponds with decagalloyl glucose, but in fact it is a mixture of polygalloyl glucoses or polygalloyl quinic acid esters with the number of galloyl moieties per molecule ranging from 2 up to 12 depending on the plant source used to extract the tannic acid. Commercial tannic acid is usually extracted from any of the following plant parts: Tara pods (Caesalpinia spinosa), gallnuts from Rhus semialata or Quercus infectoria or Sicilian sumac leaves (Rhus coriaria).

According to the definitions provided in external references such as international pharmacopoeia, Food Chemicals Codex and FAO-WHO tannic acid monograph only tannins obtained from the above-mentioned plants can be considered as tannic acid. Sometimes extracts from chestnut or oak wood are also described as tannic acid but this is an incorrect use of the term. It is a yellow to light brown amorphous powder.

While tannic acid is a specific type of tannin (plant polyphenol), the two terms are sometimes (incorrectly) used interchangeably. The long-standing misuse of the terms, and its inclusion in scholarly articles has compounded the confusion. This is particularly widespread in relation to green tea and black tea, both of which contain many different types of tannins not just exclusively tannic acid.[3]

Tannic acid is not an appropriate standard for any type of tannin analysis because of its poorly defined composition.

Quercitannic and gallotannic acids

[edit]Quercitannic acid is one of the two forms of tannic acid[4] found in oak bark and leaves.[5] The other form is called gallotannic acid and is found in oak galls.

The quercitannic acid molecule is also present in quercitron, a yellow dye obtained from the bark of the Eastern black oak (Quercus velutina), a forest tree indigenous in North America. It is described as a yellowish-brown amorphous powder.

In 1838, Jöns Jacob Berzelius wrote that quercitannate is used to dissolve morphine.[6]

In 1865 in the fifth volume of "A dictionary of chemistry", Henry Watts wrote :

It exhibits with ferric salts the same reactions as gallotannic acid. It differs however from the latter in not being convertible into gallic acid, and not yielding pyrogallic acid by dry distillation. It is precipitated by sulfuric acid in red flocks. (Stenhouse, Ann. Ch. Pharm. xlv. 16.)

According to Rochleder (ibid lxiii. 202), the tannic acid of black tea is the same as that of oak-bark.[7]

In 1880, Etti gave for it the molecular formula C17H16O9. He described it as an unstable substance, having a tendency to give off water to form anhydrides (called phlobaphenes), one of which is called oak-red (C34H30O17). For him, it was not a glycoside.[8][9]

In Allen's "Commercial Organic Analysis", published in 1912, the formula given was C19H16O10.[10]

Other authors gave other molecular formulas like C28H26O15, while another formula found is C28H24O11.[11]

According to Lowe, two forms of the principle exist – "one soluble in water, of the formula C28H28O14, and the other scarcely soluble, C28H24O12. Both are changed by the loss of water into oak red, C28H22O11."[12]

Quercitannic acid was for a time a standard used to assess the phenolic content in spices, given as quercitannic acid equivalent.[13]

In an interesting historical note, the inventor of carborundum, Edward G. Acheson, discovered that gallotannic acid greatly improved the plasticity of clay. In his report of this discovery in 1904 he noted that the only known historical reference to the use of organic material added to clay is the use of straw mixed with clay described in the Bible, Exodus 1:11 and that the Egyptians must have been aware of his (re-)discovery. He stated "This explains why the straw was used and why the children of Israel were successful in substituting stubble for straw, a course that would hardly be possible, were the fibre of the straw depended upon as a bond feasible for the clay, but quite reasonable where the extract of the plant was used."[14]

Uses

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2016) |

Tannins are a basic ingredient in the chemical staining of wood, and are already present in woods like oak, walnut, and mahogany. Tannic acid can be applied to woods low in tannin so chemical stains that require tannin content will react. The presence of tannins in the bark of redwood (Sequoia) is a strong natural defense against wildfire, decomposition and infestation by certain insects such as termites. It is found in the seeds, bark, cones, and heartwood.

Tannic acid is a common mordant used in the dyeing process for cellulose fibers such as cotton, often combined with alum and/or iron. The tannin mordant should be done first as metal mordants combine well with the fiber-tannin complex. However this use has lost considerable interest.

Similarly tannic acid can also be used as an aftertreatment to improve wash fastness properties of acid dyed polyamide. It is also an alternative for fluorocarbon aftertreatments to impart anti-staining properties to polyamide yarn or carpets. However, due to economic considerations currently the only widespread use as textile auxiliary is the use as an agent to improve chlorine fastness, i.e. resistance against dye bleaching due to cleaning with hypochlorite solutions in high-end polyamide 6,6-based carpets and swimwear. It is, however, used in relatively small quantities for the activation of upholstery flock; this serves as an anti-static treatment.

Tannic acid is used in the conservation of ferrous (iron based) metal objects to passivate and inhibit corrosion. Tannic acid reacts with the corrosion products to form a more stable compound, thus preventing further corrosion from taking place. After treatment the tannic acid residue is generally left on the object so that if moisture reaches the surface the tannic acid will be rehydrated and prevent or slow any corrosion. Tannic acid treatment for conservation is very effective and widely used but it does have a significant visual effect on the object, turning the corrosion products black and any exposed metal dark blue. It should also be used with care on objects with copper alloy components as the tannic acid can have a slight etching effect on these metals.

Tannic acid is also found in commercially available iron/steel corrosion treatments, such as Hammerite Kurust.

Use in food

[edit]In many parts of the world, its uses in food are permitted. In the United States, tannic acid is generally recognized as safe by the Food and Drug Administration for use in baked goods and baking mixes, alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, frozen dairy products, soft and hard candy, meat products, and rendered animal fat.[15]

According to EU directive 89/107/EEC, tannic acid cannot be considered as a food additive and consequently does not hold an E number.[16] Under directive 89/107/EEC, tannic acid can be referred to as a food ingredient. The E-number E181 is sometimes incorrectly used to refer to tannic acid; this in fact refers to the INS number assigned to tannic acid under the FAO-WHO Codex Alimentarius system.[16]

Uses as a medication

[edit]In conjunction with magnesium and sometimes activated charcoal, tannic acid was once used as a treatment for many toxic substances, such as strychnine, mushroom, and ptomaine poisonings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[17]

The introduction of tannic acid treatment of severe burn injuries in the 1920s significantly reduced mortality rates.[18] During World War I, tannic acid dressings were prescribed to treat "burns, whether caused by incendiary bombs, mustard gas, or lewisite".[19] After the war this use was abandoned due to the development of more modern treatment regimens.

Hazards

[edit]Tannic acid could cause potential health hazards such as damage to the eye, skin, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract. It may cause irritation, redness, pain, blurred vision, and possible eye damage. When tannic acid is absorbed through the skin in harmful amounts, it may cause irritation, redness, and pain. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea are symptoms of tannic acid ingestion and prolonged exposure may cause liver damage. Upon inhalation, tannic acid may cause respiratory tract irritation.[20]

Crocodilian coloration

[edit]Skin color in Crocodilia (crocodiles and alligators) is very dependent on water quality. Algae-laden waters produce greener skin, while tannic acid in the water from decay of leaves from overhanging trees (which produces some types of blackwater rivers) often produce darker skin in these animals.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ "Tannic acid". American Chemical Society. 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Tannic acid". Chemical Book.

- ^ Pettinga, C. (1979). "Darvon safety". Science. 204 (4388): 6. Bibcode:1979Sci...204....6P. doi:10.1126/science.432625. PMID 432625.

- ^ L'Energie Homo-Hydrogne. Editions Publibook. 2004. pp. 248–. ISBN 978-2-7483-0811-2.

- ^ "Quercus Cortex. Oak Bark". Henriette's Herbal Homepage.

- ^ Traité de chimie, Volume 2. Jöns Jakob Berzelius (friherre) and Olof Gustaf Öngren, A. Wahlen et Cie., 1838[page needed]

- ^ Watts, Henry (1868). A Dictionary of chemistry and the allied branches of other sciences. Vol. 5. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 6.

- ^ Etti, C. (1880). "Über die Gerbsäure der Eichenrinde" [About the tannic acid from oak bark]. Monatshefte für Chemie (in German). 1 (1): 262–78. doi:10.1007/BF01517069. S2CID 94578197.

- ^ Etti, C. (1883). "Zur Geschichte der Eichenrindegerbsäuren" [On the history of oak bark tannins]. Monatshefte für Chemie (in German). 4 (1): 512–30. doi:10.1007/BF01517990. S2CID 105109992.

- ^ Smith, Henryl. (1913). "The Nature of Tea Infusions". The Lancet. 181 (4673): 846. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)03766-7.

- ^ Reckford, Courtney (1997). What are the historic and contemporary ethnobotanical uses of native Rhode Island wetlands plants? (PDF) (MA Thesis). OCLC 549678548.[page needed]

- ^ Sayre, Lucius E. A manual of organic materia medica and pharmacognosy: An introduction to the study of the vegetable Kingdom and the vegetable and animal drugs (PDF) (Fourth ed.). p. 95.

- ^ Putt, Earl B.; Seil, Harvey A. (2006). "Government standards for spices". Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association. 12 (12): 1091–4. doi:10.1002/jps.3080121212.

- ^ Acheson, Edward G. (1904) "Egyptianized Clay" in Transactions of the American Ceramic Society. pp. 31–65.

- ^ "Food Additive Status List (GRAS); listing for tannic acid". US Food and Drug Administration. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ a b EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (2014-10-01). "Scientific Opinion on the safety and efficacy of tannic acid when used as feed flavouring for all animal species". EFSA Journal. 12 (10): 3828. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3828.

- ^ Sturmer, J. W. (April 13, 1899). "Pharmaceutical Toxicology". The Pharmaceutical Era. 21: 472–4. ISSN 0096-9125.

- ^ "The use of tannic acid in the local treatment of burn wounds: intriguing old and new perspectives". Wounds. 13 (4): 144–58. 2001.

- ^ "Medicine: War Wounds". TIME. 18 September 1939. Archived from the original on May 30, 2008.

- ^ "Material Safety Data Sheet: Tannic Acid". fscimage.fishersci.com. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ "American Alligator: Species Profile". National Park Service. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

General references

[edit]The Merck Index, 9th edition, Merck & Co., Rahway, New Jersey, 1976.